|

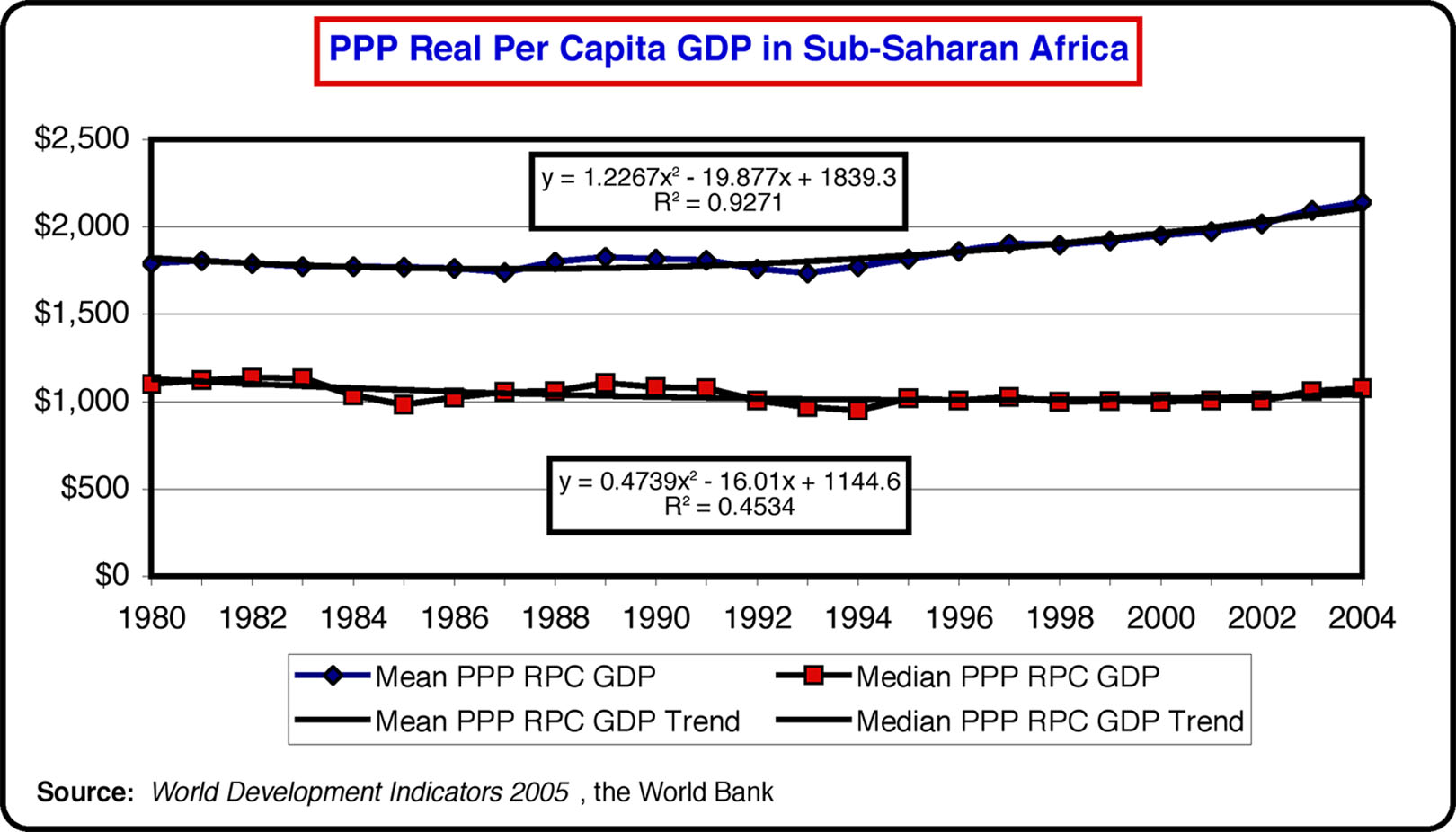

While mean per capita GDP in Sub-Saharan Africa has grown, median levels have hardly increased since 1980.

|

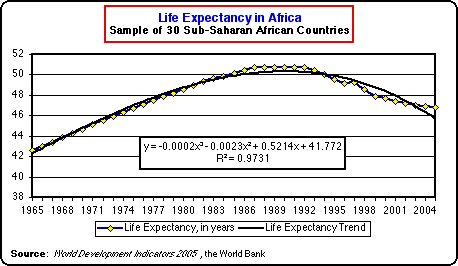

Life expectancy rates in Sub-Saharan Africa peaked in the late 1980's and have been falling since. Part of this decline is due to rising poverty rates, and part of the change in due to Africa's relative high HIV rates, which are nine times the next highest region's infection rates.

|

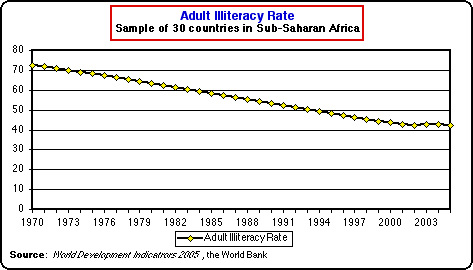

One positive factor in combating poverty and HIV infection is literary, particularly among adults in general, and women in particular. Yet, despite substantial declines in illiteracy, the expected effects on health conditions have not yet materialized.

|

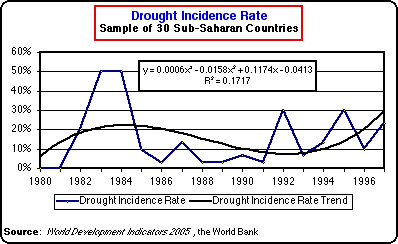

One common explanation for Africa's weak economic performance is the incidence of drought. World Bank data suggest that drought may take place in cycles, but the current picture is one of fewer incidents of drought than in the 1980s.

|

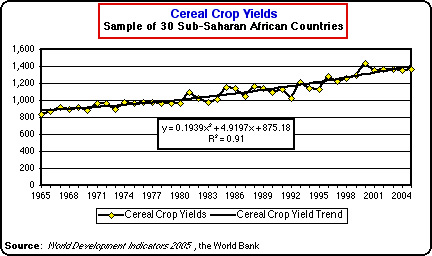

Another positive indicator is that agricultural productivity in Africa has continued a steady upward trend. While most countries are far from self-sufficient in food production, continued progress in raising yields is essential not just to food security, but also in reducing the incidence of poverty.

|

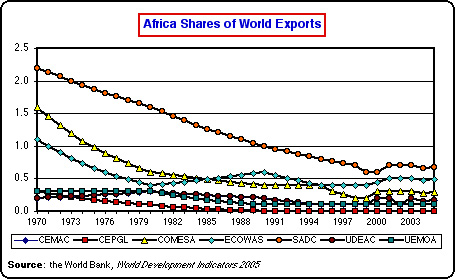

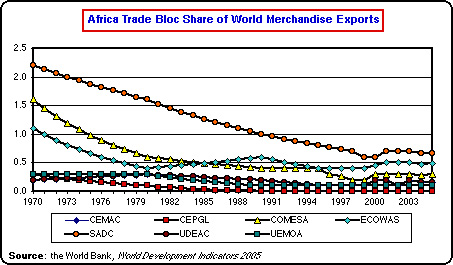

Even though African countries have made progress in raising agricultural productivity, African exports, which are concentrated in primary agriculture and minerals, have declined in relative terms, particularly in comparison to the export economies of East Asia

|

This decline can be further noted in terms of Africa's declining share of world merchandise exports.

|

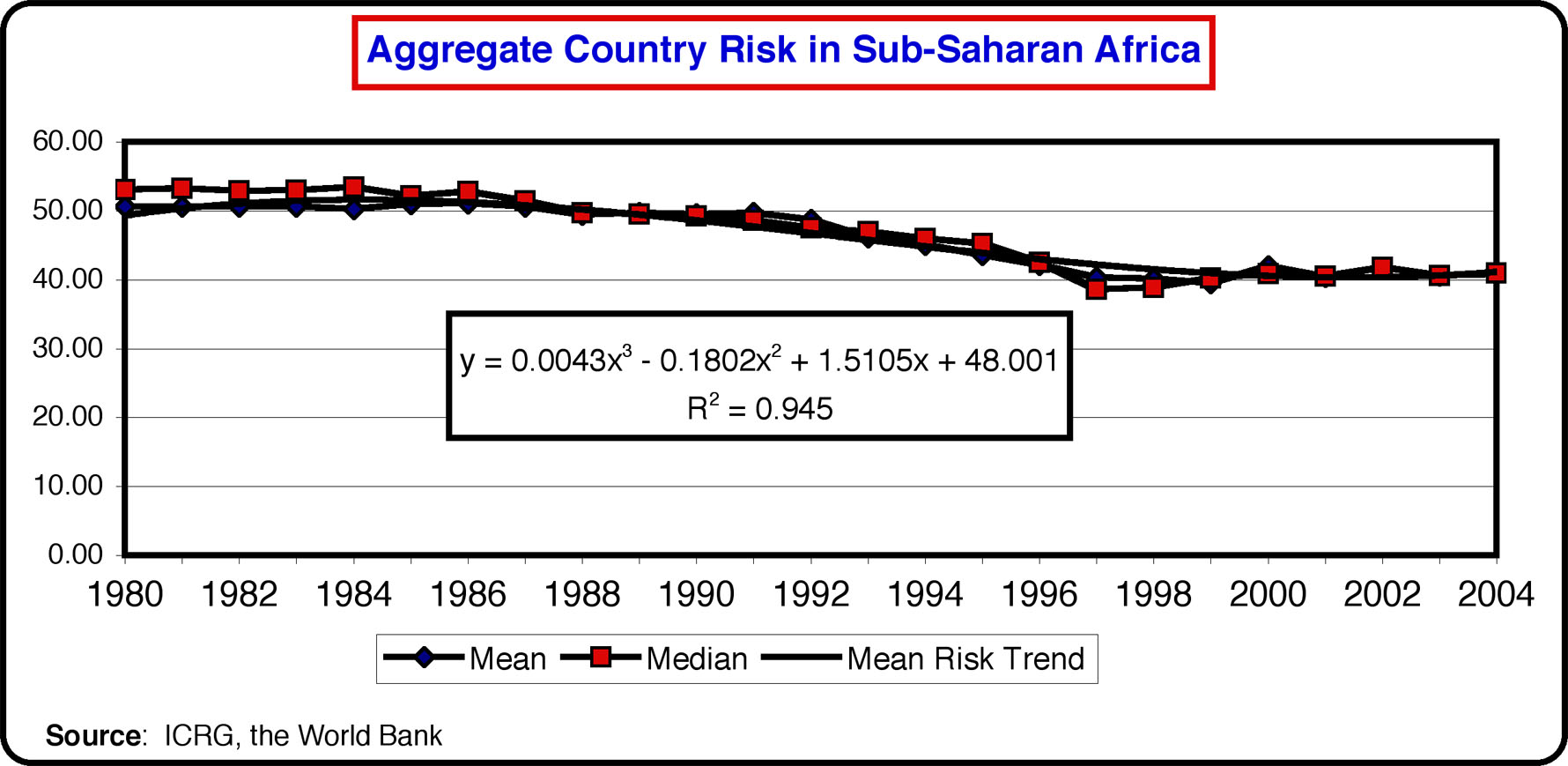

Against this backdrop, standard policy prescriptions have often fallen short of raising real per capita income in Africa. In our view, this can be explained largely in terms of the presence of risk in economic and financial decision-making. Absent sovereign capital markets, one proxy measure of the level of risk is the ICRG aggregate country risk level, which is a composite of political, economic, financial, and environmental risk. For African countries, aggregate risk is greater than for other parts of the world, and has even declined somewhat during the past 20 years. Yet its relatively higher level suggests that institutional reforms may be a key to bringing about further reductions, which in turn would bring about higher levels of per capita income.

|

|

Where risk is present, it is usually accompanied by institutional corruption. The Corruption Perceptions Index provides a measure of perceived levels of corruption. For African countries, while some reductions did occur toward the end of the 1990s, there has been a recent upturn, which suggests that aggregate country risk may also be on the rise.

|

|

Corruption and risk are detrimental to economic growth. One determinant of the level of corruption and risk is the level of judicial independence. Judicial independence means that contract decisions are removed from political influence. Measures that strengthen judicial independence are thus one important step in reducing corruption and risk in an economy.

|

|

Economic freedom, as measured by the Wall Street Journal and the Heritage Foundation's Index of Economic Freedom, consists of a number of dimensions that shape the economic and financial climate. It includes measures pertaining to government deficits, price distortions, contract execution times, and other factors that add to (or subtract from) to cost of transactions. While some declines in economic freedom were noted for the 1990s, African economies experienced increases in the beginning the 2000 period, but which now may be under erosion as economic and political uncertainty has increased in many countries.

|

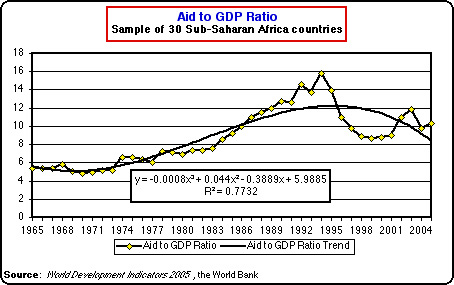

Some have argued that aid is both the problem and the solution for Africa's economic performance. What is clear is that the international Aid to GDP ratio has risen for most of the last thirty years, a period when Africa's economic performance showed little difference. While it has lately been in decline in favor of efforts to generate higher local foreign direct investment and the promotion of domestic capital markets, it may once again be on the increase as economic reforms fail in both scope and magnitude.

|

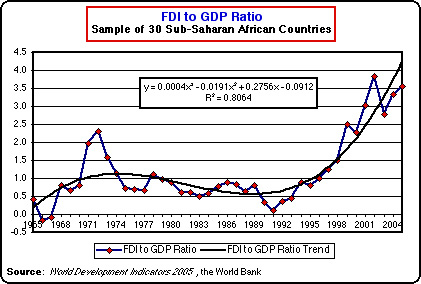

One positive measure of economic reform is the increase in foreign direct investment in Africa. While miniscule in comparison to FDI flows to North America, West Europe, and East Asia, the fact that is has been on an upward trend may yet produce positive results for local economic growth.

|

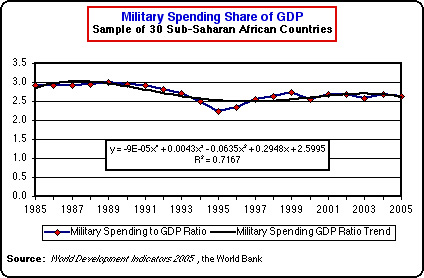

One determinant of international aid is the level of local spending on national security. African countries have generally spent lower shares of GDP on national security than the US, but these rates are still far higher than for most countries in East Asia.

|

|

While judicial independence is essential to sustainable growth, another factor is how legal systems uphold property rights. Property rights in Sub-Saharan Africa are much weaker than in many other parts of the world. When combined with a weak judicial system, the absence of credible property rights undermines domestic investment, foreign investment, and other measures that are essential to sustainable growth. This finding has been well documented by the Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto in The Other Path and in The Mystery of Capital, in which he analyzes in some detail how capital resources in many developing countries are immobilized by the absence of such things as clear titles to land use. That property rights in Africa have been in decline does not bode well for future economic growth.

|

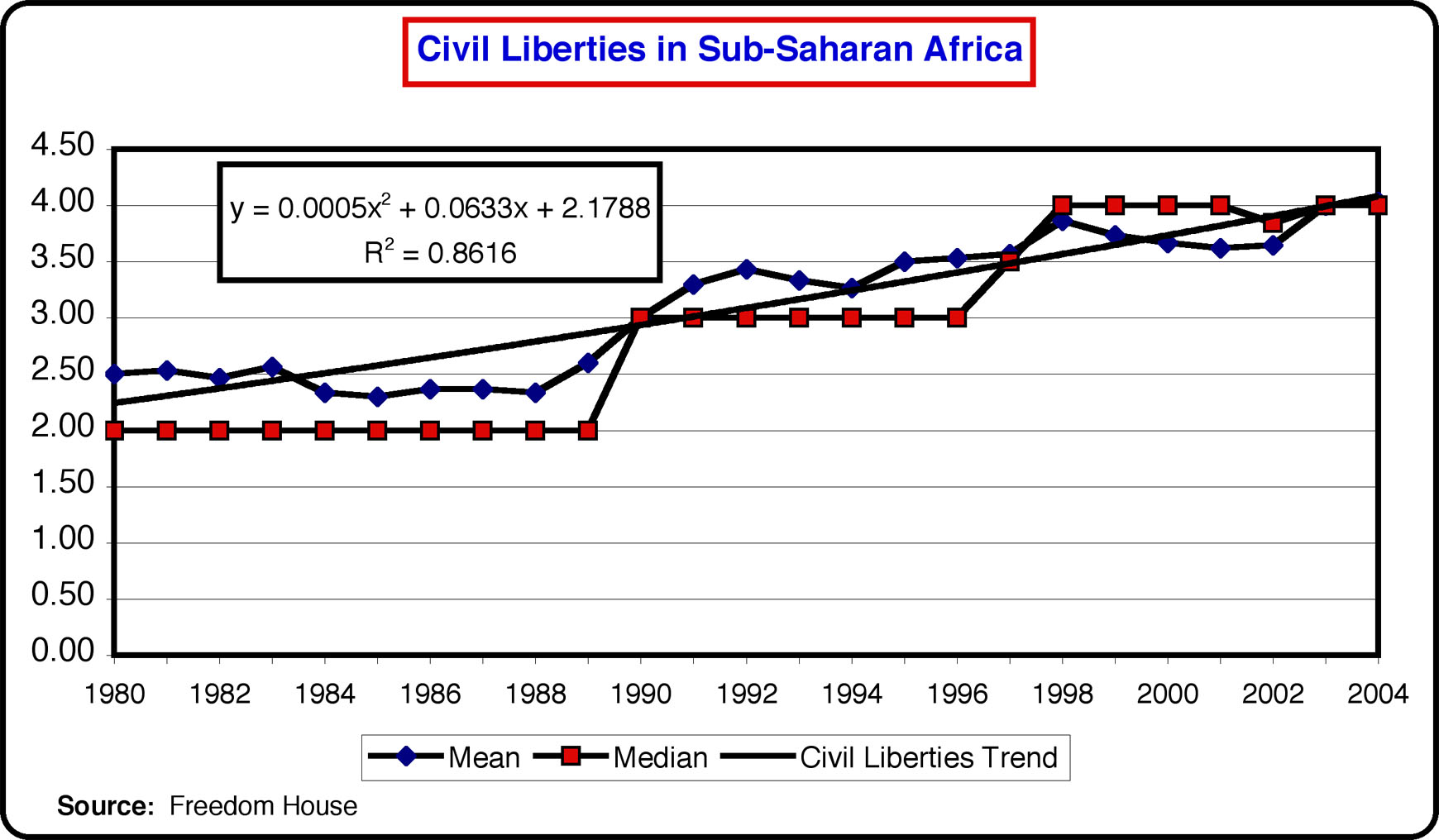

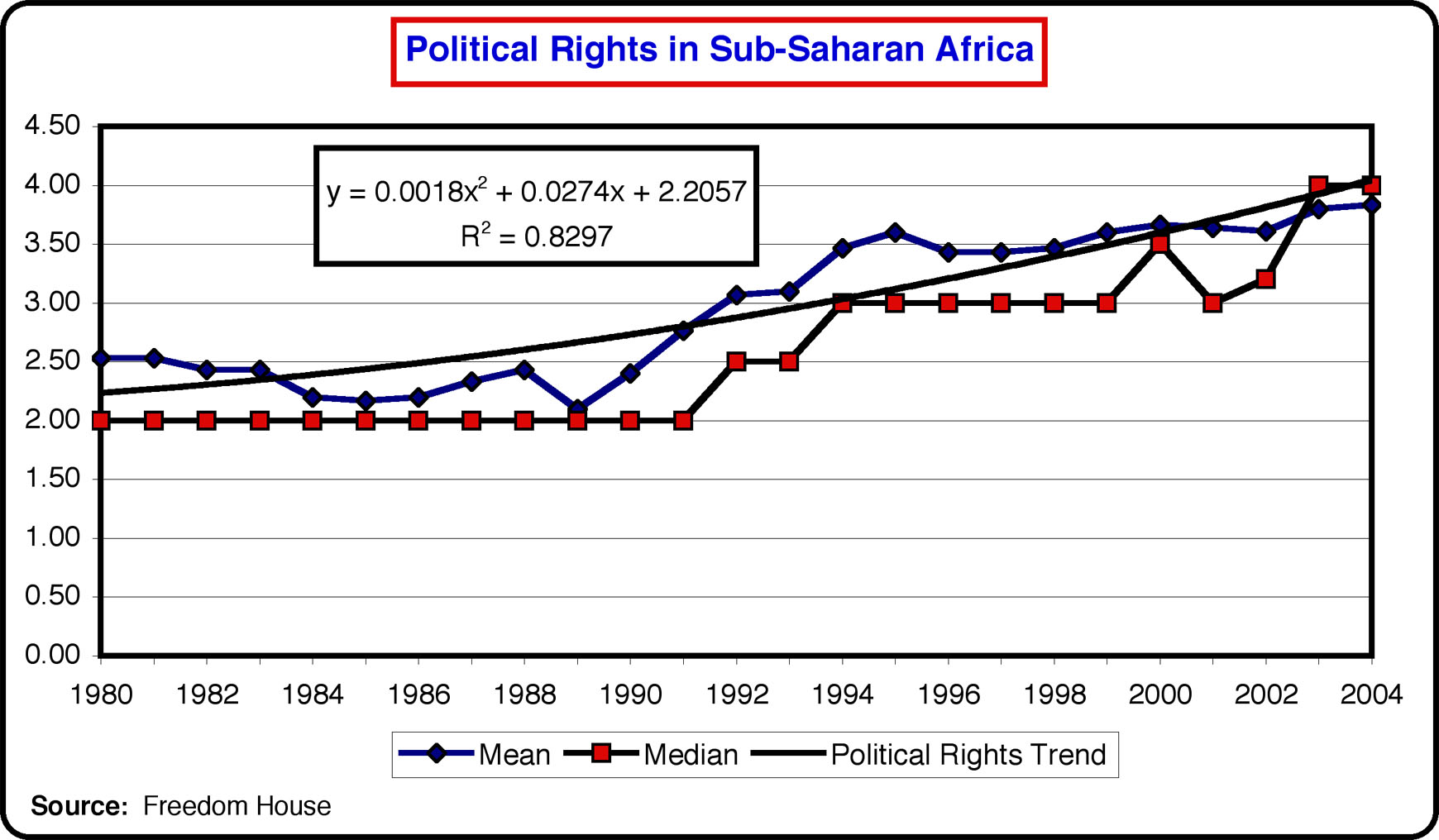

Some have argued that if economic freedom has been limited in Africa, it is because civil liberties, political rights, and the general level of democracy has been weak. While many African countries still have authoritarian regimes, there has been a steady increase in civil liberties, as has been tracked by Freedom House in its annual survey of Freedom Around the World.

|

As compiled by Freedom House, both civil liberties and political rights have been increasing in Africa. The question is whether the expansion of these rights, and the associated level of democracy, contributes substantially to expanding the level of per capita income.

|

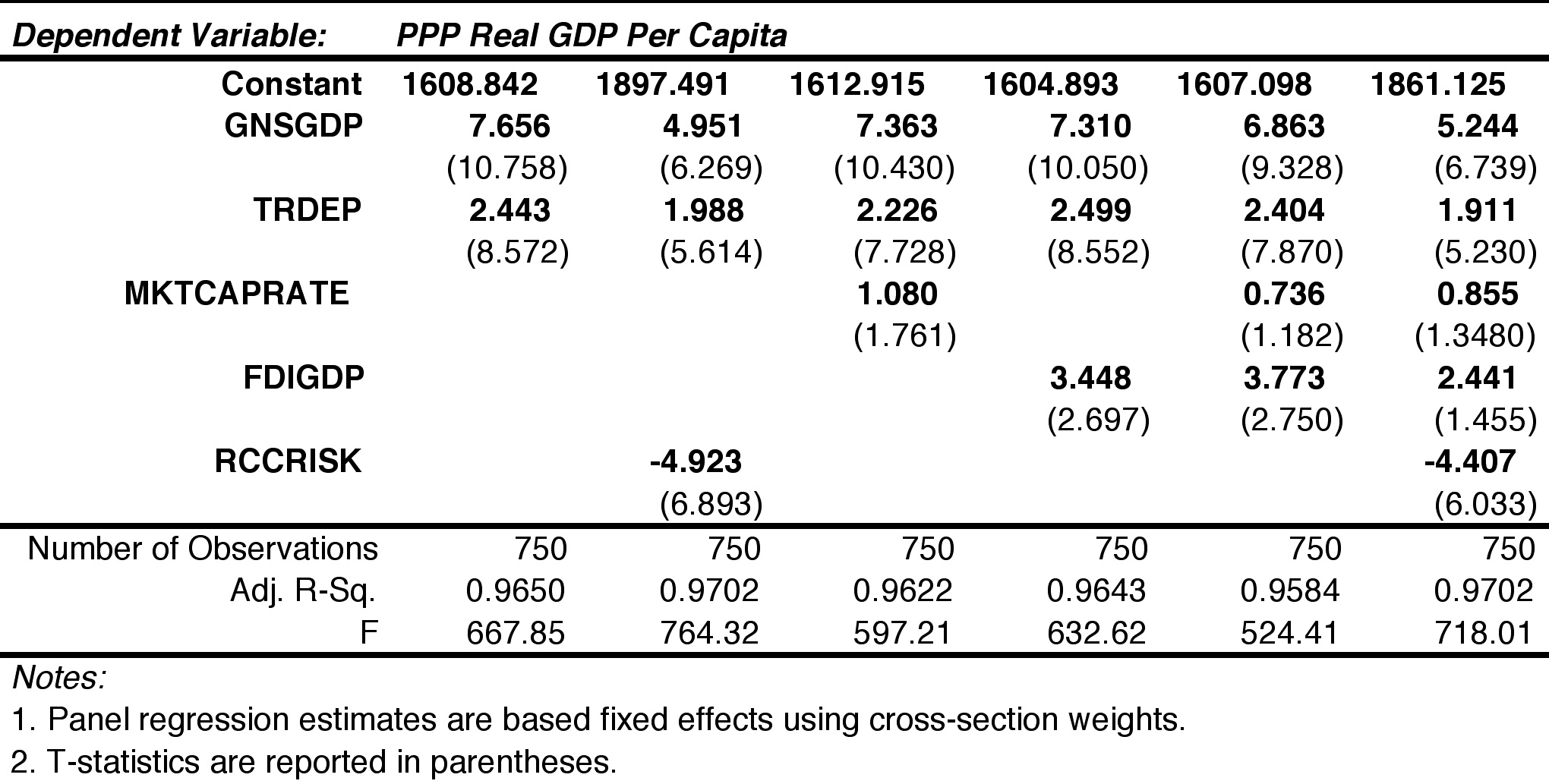

We now examine through a panel regression model some of the underlying determinants of economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa:

While a country's saving rate, its trade dependency, its market capitalization rate, and the level of foreign direct investment are important to economic growth, the negative effect of aggregate country risk is the singlemost offsetting factor, which suggests that institutional governance is crucial to the success of these factors in achieving economic growth.

|

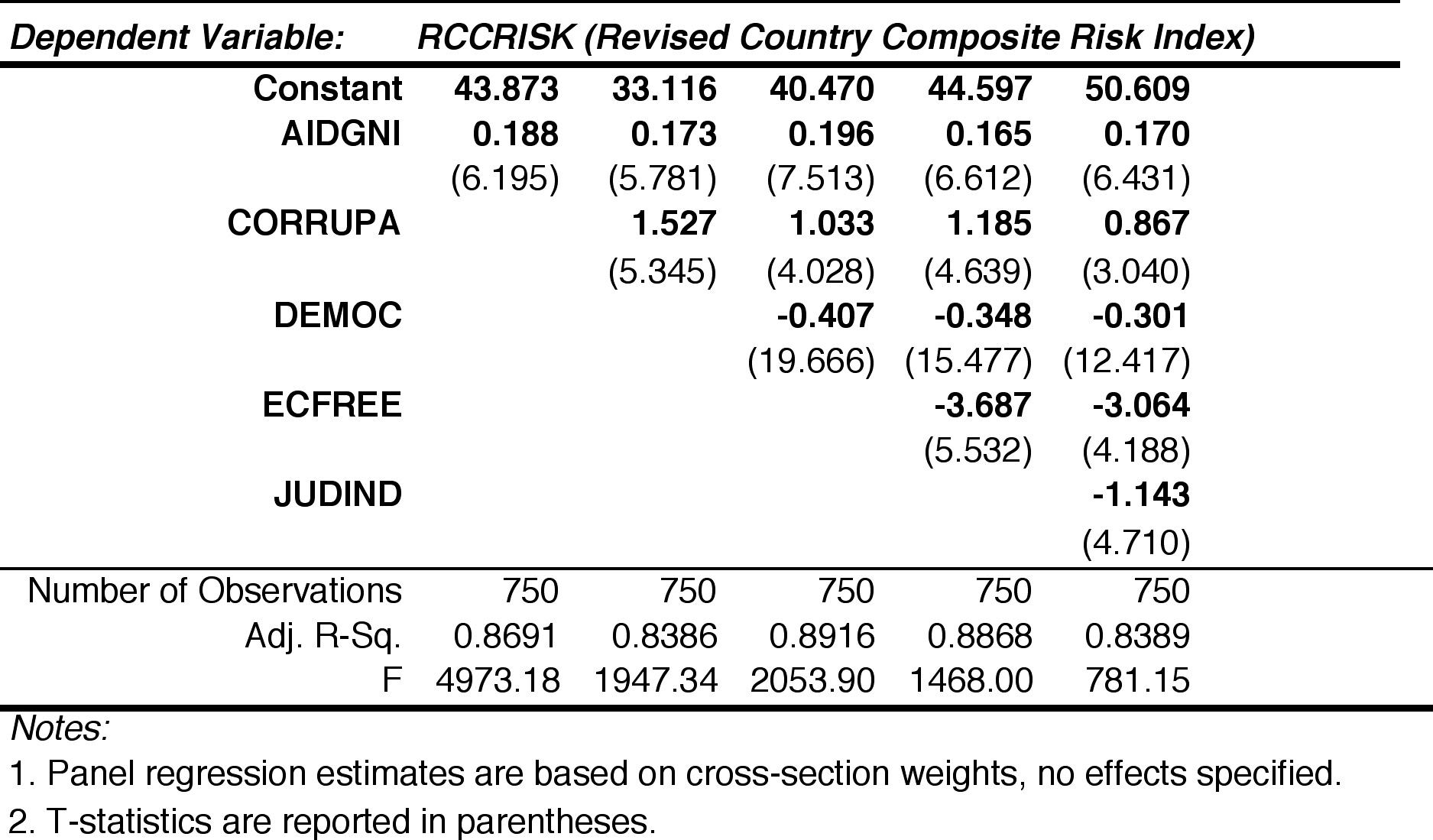

If risk is a critical determinant of risk, we also look at its determinants. We find that the level of corruption, democracy, economic freedom, judicial independent, and the level of international aid are important factors. What needs to be done is to establish a hierarchical sequence of causality to determine in what order these factors play a role in shaping the level of aggregate country risk.

|

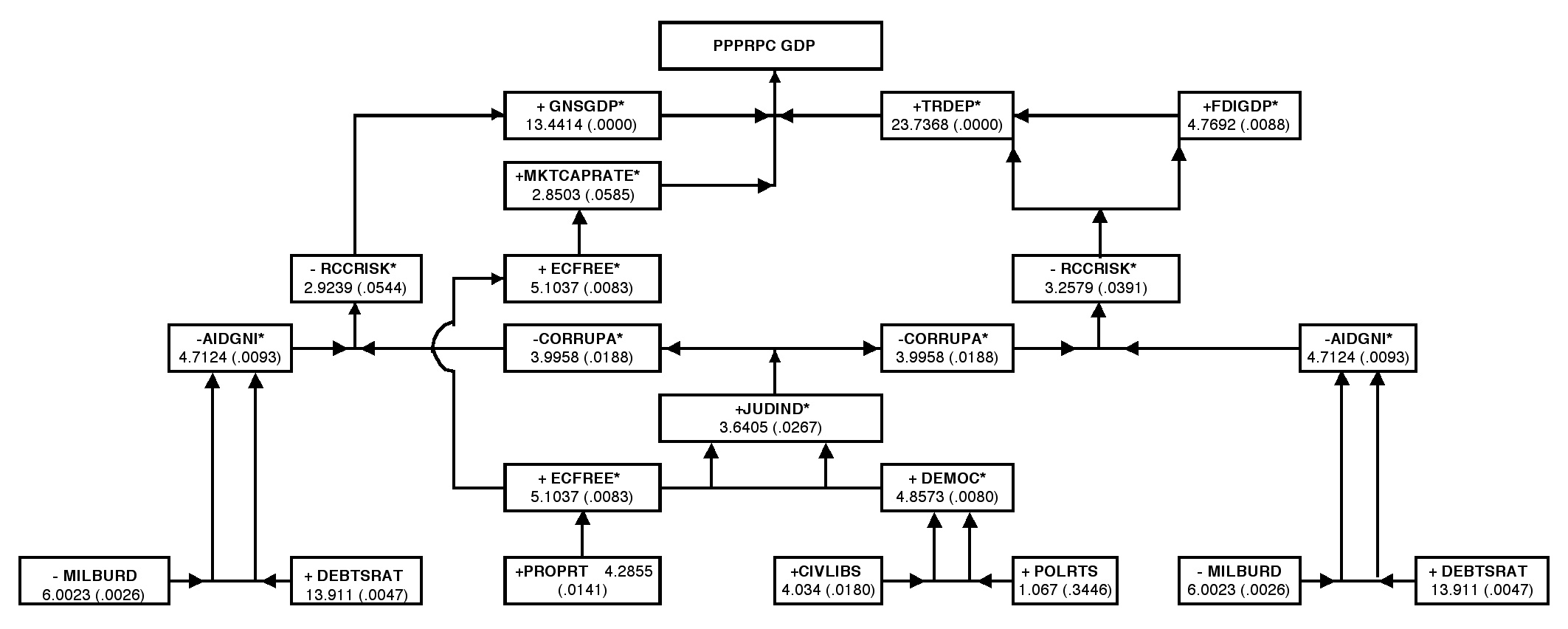

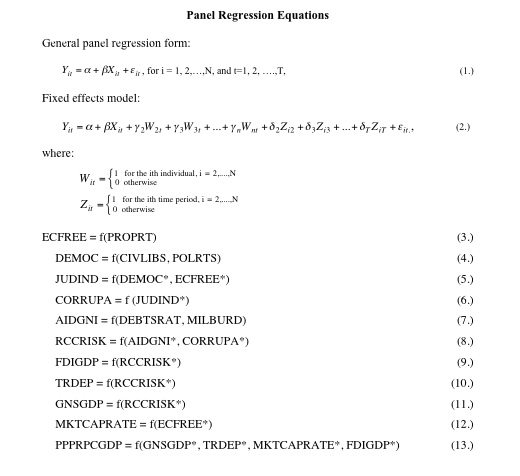

| To establish the hierarchical sequence, we apply Granger causality tests to the basic variables under review. The resulting structure of our nested panel regression model is presented below:

|

| We now apply panel regression estimates of the various determinants in the model. The structure of the panel regression used here is given as:

|

Regression results for our basic model are:

|

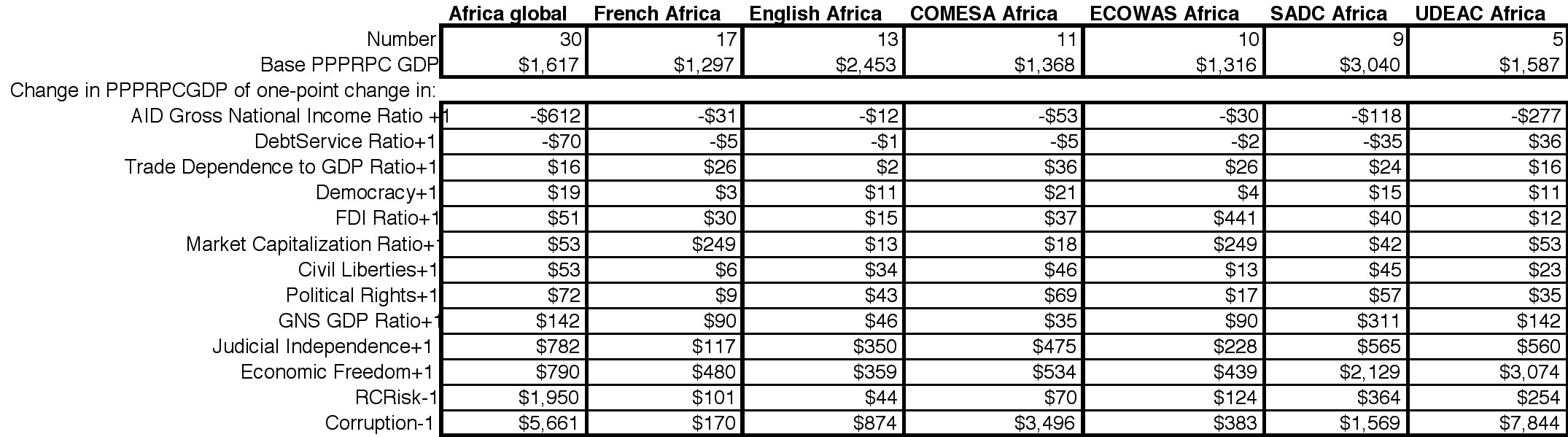

| Using the nested estimating equations, we now derive the effect of one-point changes in various determinants on the level of PPP Per capita GDP:

As can be seen, while reductions in risk and corruption produce the largest effects on per capita GDP, these variables are in turn affected by changes in divil liberties, political rights, property rights, and judicial independence.

|

| We also re-computed nested panel regression estimates for various sub-groupings. Results for these groupings are shown in descending order of the number of countries by type of configuration:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A profile of the 30 African countries used in this study is given here:

|

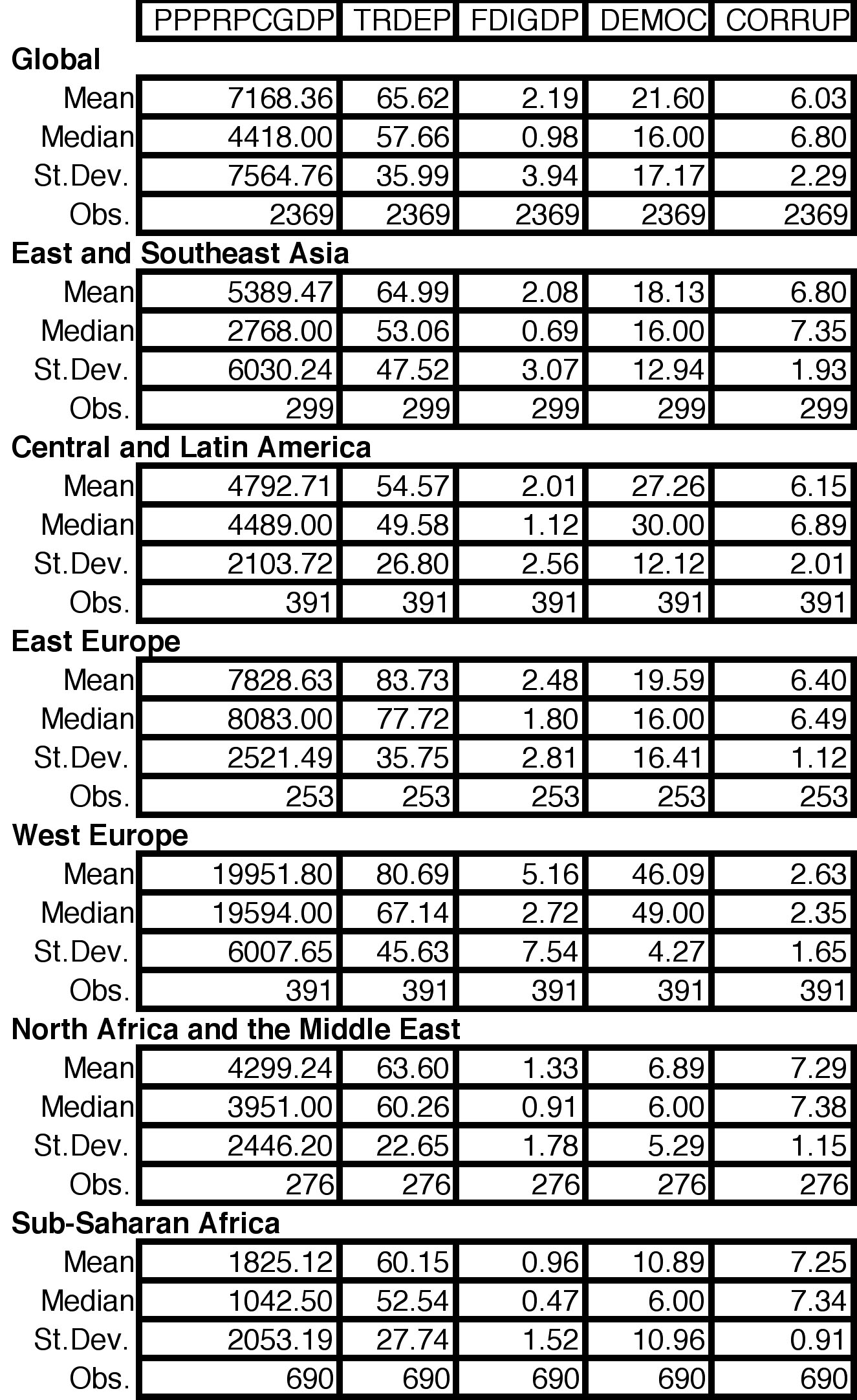

| Descriptive statistics of the variables used in the study are given here:

|

| Model variable definitions, scales, and sources are given here:

|

Some comparative indicators by region:

|