Click to see the list of links

290) Attitudes toward our ongoing project

Ludwik Kowalski; 4/5/2006

Department of Mathematical Sciences

Montclair State University, Upper Montclair, NJ, 07043

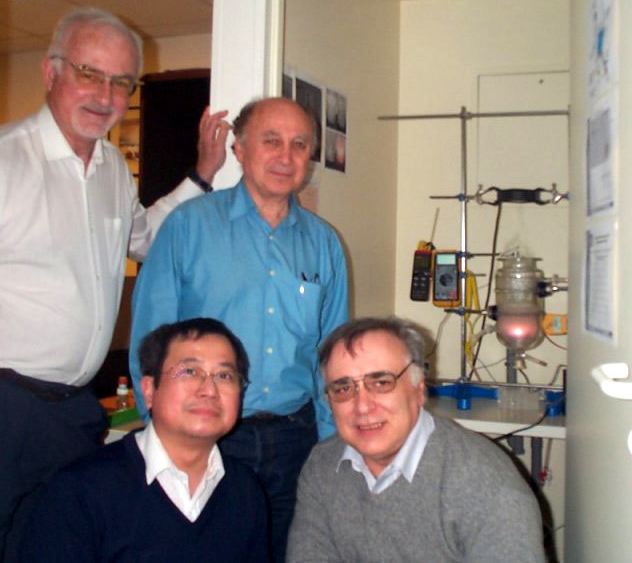

1) This morning Pierre sent me a picture which I see think is worth posting. Pictures of other researchers, with whom I had privilege of working on

the ongoing CMNS project (Scott Little and Richard Slaughter) have already been posted in unit 270. The picture below shows Pierre Clauzon (upper

left) and Gerard Lalleve (lower right). Also shown are Jean Paul Biberian (upper right) and Jean Louis Naudin (lower left). Jean Paul might start

a new Mizuno-type experiment in Marseilles soon while Jean Louis is a veteran in the field of plasma cells, as indicated in the unit #289.

Do not miss a Mizuno-type cell on that photo. It is next to Gerard’s head. The red-orange spot is the glowing plasma column at the tip of the cathode. The next photo shows Ed Storms (left side) and Fangil Gareev (right side). I took that picture December 2006, at our last conference in Japan (ICCF12). Gareev is from the Nuclear Research Laboratory in Dubna, Russia.

And how could I not show the photo of me with Russian friends? On the right side is Alexander Karabut, then the interpreter Natalia Famina, then myself, and then Irina Savvatimova. Discoveries of Karabut and Savvatimova, described in the unit #13, had profound effect on me. The picture below was taken December 2006, at our last conference in Japan.

A) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

So much about pictures. Now I would like to show the unexpected message that Ed Storm posted on the restricted discussion list for CMNS researchers.

“ I want to add emphasis to what Jed said and reiterate what I have been saying in previous e-mails. Trying to do CF

experiments on the cheap and with crude equipment is a complete waste of time. Like most people in the field, I started this way and have regretted

it ever since. After many years of trial and error, and on the job training, many of us know what works and what does not. It is essential that

this experience be used unless you want to spend years getting this experience yourself. The advice is to use standard, well understood methods;

use equipment that is reliable; and design the experiment so that it is as simple as possible.

On the other hand, I see that it is hard for some people to take such advice. People seem to be designed to insist on doing an experiment their

own way so that they can express their own creativity. Perhaps, making mistakes and learning the lessons are required for everyone. That is why

actually running an experiment teaches more than any amount of advice. Only failure gives interest in making a change in the approach.”

B) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

And here is my immediate reply to this message. “Ed, instead of arguing in general let me review our specific situation.

1) A claim was made (Paris-1) that a very simple method can be used to demonstrate excess heat. What should be the most natural way to check this?

It is to perform the identical experiment and look for results.

2) We did this in Texas-1 and in Colorado-1. Results did not confirm excess heat. Our report at ICCF12 was criticized for not performing the experiment

in the same way as in Paris-1. A researcher from the Paris-1 team, Pierre Clauzon, came to help us to replicate their experiment properly. Under his

guidance we were able to observe excess heat. We confirmed that identical, more or less, results are obtained under identical conditions.

3) This was a big step forward. In any other field of science we would write a paper and this would probably be viewed as a small step forward. Other

researchers, or ourselves, would then start performing better experiments to explore various aspects of the natural phenomenon, including practical

applications.

4) But, as you know very well, it is not easy to publish results of CMNS investigations in a refereed journal. Facing this situation, we do not have

the luxury of being satisfied by publishing the results. Our work is unfinished. Starting another project, for example an experiment in a closed cell

with a flow calorimeter, would mean that we simply wasted time. We want our results to be known, as they are, not as they might be in another

experiment. If we are right then we want to convince others that we are right. If we are wrong then we want to know where we are wrong.

5) I think the methodology chosen for the Paris-1 experiment was appropriate to investigate the COP>1.2; it would not be appropriate for the

COP<1.05. The claimed signal is said to be large, and systematic errors of 2% or 3% should not prevent a researcher from identifying it. After

all, the energies to measure are in the range between 30 KJ and 100 KJ.

6) We performed about 50 evaluations of the COP and found the results to be reproducible. The mean value was 1.24 and the standard deviation was 0.13.

Preliminary Paris-2 and Colorado-3 results (at least ten measurements, as I know from private messages ) are consistent with these data.

7) Why should we abandon the methodology which produces credible results? Why should we not continue searching for possible systematic errors? Perhaps

there are no large errors; perhaps the true value is somewhere between 1.1 and 1.3. We want to know this for sure.

8) You wrote: ‘Trying to do CF experiments on the cheap and with crude equipment is a complete waste of time.’ I

do not think that we were wasting time. Our instruments are not too crude. You also wrote “The advice is to use standard,

well understood methods; use equipment that is reliable; and design the experiment so that it is as simple as possible.” That is what we

were doing. We measured temperatures with a standard student laboratory thermometer, we measured the mass lost with a standard digital laboratory scale,

we measured electric energy by several standard methods and verified that differences between these methods were very small.

9) I suspect that our weak points are in the interpretation, not in measurements. Fortunately, voices on this list helped us to identify two weak

points: (a) absence of determination of the amount of liquid lost in the form of tiny droplets and ( b) the possibility that the measured excess heat

is due to well known chemical reactions.

10) It is always better when such issues are recognized before a paper is submitted. In our situation this is essential. We must address the weak

points in the paper before the referees identify them. Unfortunately, we are not chemists. That is why help from chemists and electrochemists is

expected. With help we might be able to succeed; without help and encouragement we might fail. Just imagine what might possibly happen after excess

heat, in a Mizuno-type experiment, is recognized as real by mainstream scientists, by the DOE, the NSF, and the editors of leading journals. Yes, I

know that our paper will not produce spectacular results. But it might be a successful first step toward recognition. Then more sophisticated

approaches will be justified. Giving up at this stage would be a big mistake.”

C) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I waited for the reply from Ed but what came instead was a message posted by Jed Rothwel. I wander what Ed Storms thinks about Jed’s message.

It is shown below. Note that what is attributed to me is in black while what is from Jed is in blue. Rothwell wrote:

Ludwik Kowalski wrote:

1) A claim was made (Paris-1) that a very simple method can be used

to demonstrate excess heat. What should be the most natural way to

check this? It is to perform the identical experiment and look for results.

That is a good first step.

A researcher from the Paris-1 team, Pierre Clauzon, came to help us

to replicate their experiment properly. Under his guidance we were

able to observe excess heat. We confirmed that identical, more or

less, results are obtained under identical conditions.

Good on you, as they say in Sydney.

3) This was a big step forward.

Well, it is replication #5 or so. Not bad, and it calls for round of applause, but it has not pushed the state-of-the-art or

added any knowledge yet.

4) But, as you know very well, it is not easy to publish results of CMNS investigations in a refereed journal.

"Not easy" is incorrect. It is utterly impossible, and if your goal is to publish in a refereed journal you are

wasting your time. I think your goal should be to convince qualified people that your results are real, not artifactual.

Facing this situation, we do not have the luxury of being satisfied by publishing the results. Our work is unfinished. Starting another project, for

example an experiment in a closed cell with a flow calorimeter, would mean that we simply wasted time.

No, it would mean that you learn the technique and you are ready to begin a more serious experiment.

We want our results to be known, as they are, not as they might be in another experiment.

Why? Ohmori's results are already known. You have not improved upon him or proved anything he did not prove long ago. This is

kind of like building an exact replication of the original 1903 Wright Flyer, to prove that airplanes can fly. Why not build a better model? why repeat

crude experiments that were performed years ago? Ohmori had no choice -- he had no money and he faced enormous opposition from the University -- but

you can use a proper computer, a digital camera to record the appearance of the plasma, multiple thermocouples or a Seebeck calorimeter. Why should

you limit yourself to instruments that were available in 1890? I cannot see any logic or any reasons for this.

5) I think the methodology chosen for the Paris-1 experiment was appropriate to investigate the COP larger than 1.2

Okay it is "appropriate to investigate." But if you want to convince large numbers of people, or if you want to learn

much more about the reaction, you will use better instruments.

We performed about 50 evaluations of the COP and found the results

to be reproducible.

Good. You are about the fifth group to confirm Ohmori, using

a method similar to his, albeit with less skill and care than he

used. If that is all you want to accomplish than you are finished

and you can stop doing the experiments.

6) Why should we abandon the methodology which produces credible results?

Because we already have credible results! Why continue with a methodology that has been tapped out and has taught us all that it

can teach? Why repeat old experiments that were already as convincing? There was never any doubt that Ohmori and Mizuno were reporting honestly, and

that they did observe apparent excess heat. I saw it myself in their labs on many occasions. Your confirmation does little to buttress their credibility,

and it adds nothing to our knowledge of this phenomenon.

Ed wrote that “trying to do CF experiments on the cheap and with crude equipment is a complete waste of time. ”I do not think that we

were wasting time. Our instruments are not too crude.”

They are way too crude. Take it from Ed -- and Mizuno, and me for that matter.

Ed wrote “The advice is to use standard, well understood methods; use equipment that is reliable; and design the experiment so that it is as

simple as possible.” That is what we were doing.

You are certainly not using well understood methods or reliable equipment. You roached your computer! How reliable can that be?

(I mean you burned it up -- in 1960s jargon.) As for simplicity, perhaps Storms should have said, as Einstein did, "as simple as possible, but

not too simple."

We measured temperatures with a standard student laboratory thermometer, we measured the mass lost with a standard digital

laboratory scale, we measured electric energy by several standard methods and verified that differences between these methods were very small.

Yes, so did Ohmori and Mizuno, many years ago. Why do you think Mizuno stopped doing this long ago? Because the method has

many inherent disadvantages and inaccuracies, as I have explained time after time.

D) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Johnny Coviello wrote:

. . . No reason to continue raising the same objections over and over again, once they are acknowledged by the researchers.

Certainly, the researchers reporting this recent excess heat result in Colorado were open to criticism of their experimental methods. Ludwik even

said that due to the rather crude nature of calculating excess heat, the experiment results under COPs of 1.20 should be considered suspect. Of course,

many of their results were above COP 1.20, so once again the chemical explanation or other error explanations, such as misting due to the violent

nature of the reaction, might not be adequate.

Look at it this way. The Colorado experiments are another indication that something unusual is occurring in these cells. If they did not record

unusual COPs, then there would be nothing to talk about. All they can do is take the criticisms into account and design another cell that tries to

address the pontial error concerns, and see if unusual COPs are once again recorded. Process of elimination. It does appear to me that a reproducible

cold fusion experiment might be evolving from the original Muzino work.

E) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Jed Rothwell wrote (in black):

He was referring to a message from Michel Jullian (see quotations in blue).

Ed, instead of patronizing and stigmatizing . . .

Storms has been doing this for 16 years. Take his advice or leave it, but stop acting childish.

. . . please note that the simple and inexpensive (for wide replication) . . .

Define inexpensive. $50? $500? $2,500? What advantage would there be in saving $2000? I cannot think of any. How widely do you want this to be

replicated, anyway? I do not think we should encourage large numbers of people at home to try an experiment that calls for boiling poisonous

electrolyte, 3000°C metal, and which

has been known to explode violently without warning for no apparent reason. Someone could be seriously hurt or killed doing this. You should think

about liability before you go around promoting replications by inexperienced people outside of well-equipped laboratories.

but rigorous (for indisputability)

If you want something indisputable, you will have to use more sophisticated techniques and better instruments that Ohmori did. Frankly, his experiment

was better than the one described here. He has skill and decades of experience. As long as you stick with inexpensive 19th-century

techniques, you will not improve on what he did, and you will not prove anything he did not prove

years ago. That is why Mizuno went on to use more sophisticated techniques.

. . . boiloff Mizuno experiment we are trying to design in this collaborative way has never been done before, so if it can be

done at all it will require creativity obviously . .

You have that backward. You are being too creative. To do this experiment properly you need to be less creative and more willing to take advice from

experts and do things according to the textbooks.

. . . i.e. lots of many silly complicated proposals which don't work before reaching the clever simple one which will work.

Cleverness is not called for. People do not believe clever results. We have already described techniques that will work. Your best choice would be a

large Seebeck and a closed cell (perhaps a reflux cell).

F) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

L. Kowalski:

We can not address all issues . . . Our experiment produced some results and I want to know if the COP=1.24 (st. dev.=0.13) is not an illusion due

to an error. I am certainly not going to discourage others from perform better experiments. And I will be extremely happy when they come up with results

that are more trustworthy, for example, COP=1.75 (st. dev. 0.03). General problems are worth discussing . . . I hope that your comment on my reply to

Ed will generate an interesting discussion. The issue -- why bother with what has already been done? -- is well framed in your message.

G) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Michel Julian (responding to a message from ED that have not seen):

Ed is quoted in blue, Michel’s comments are in blue.

Dear Ed, my comments in your text. (To Jed and JCJ, less verbal violence please)

Dear Michel, I do not mean to be insulting. My comment was a simple observation

No insult taken then. Sorry I misinterpreted your comments. [What follows is from from another message of Michel]:

Group, assuming we all agree on the objective of the simplest possible indisputable boiloff Mizuno experiment design, we could discuss honestly and

peacefully the merits of all proposals, giving priority at any given time to the simplest that is currently proposed (which should take the least time

to debunk), and working our way progressively up through the more sophisticated ones as and if we find flaws in the simpler ones. The metric for simpler

could be that more people can replicate the experiment, based on the bill of materials.

We should try to refrain from any preference based on whether the solution is 19th century or 21st century, nor whether it was invented here or there,

nor whether the proposer has been 17 years or 1 month in the field, nor whether he has scientific/technical education or not, nor whether he can shout

louder than another. Merits only.

If we don't understand a proposal we should say so rather than ignoring it, and the proponent should explain. Critical sense would be welcome. Flames

or patronizing wouldn't. . . .

H) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Jed Rothwell:

Michel Jullian wrote: “The metric for simpler could be that more people can replicate the experiment, based on the bill

of materials.”

Why would the bill of materials be the limiting factor? I should think that an easier, safer, more certain method would increase the number of people who

can replicate. Whether an experiment cost $1,000 or $5,000, and whether it takes 5 components or 20, seems immaterial.

[He also wrote: ] “We should try to refrain from any preference based on whether the solution is 19th century or 21st century

. . .”

Indeed, why stop at the 19th century? Let us consider using 18th century techniques to refine our own tungsten from wolframite. I assume the goal of this

technological time travel is to make life difficult, create extra labor, and reduce precision, so that when we return to the 21st century with a sigh of

relief, we will appreciate computers, thermocouples and the other 'tools of advanced civilization' (what the Japanese call 'bunmei no riki'). It is sort

like camping, in other words. I myself spent enough time in the pre-computer world of typewriters, slide-rules, film-cameras and mercury thermometers.

Nostalgia aside, I have no desire to reenact it.

[He also wrote: ] “ nor whether it was invented here or there, nor whether the proposer has been 17 years or 1 month in the

field, nor whether he has scientific/technical education or not . . .” Another interesting suggestion! Ah, but consider -- (a) "Those

who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it." - George Santayana [and] "Experience is a dear teacher, but a fool will learn at no

other." - Benjamin Franklin

G) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Ed Storms wrote:

Of course a machine shop is required along with a glass blower and a computer programer. Without either the money to hire such people or the personal

ability to do the job, you should not be in the business of trying to prove that an unbelievable effect is real. In the good old days when I learned

science, everything had to be designed and constructed by the experimenter. Now, a great deal can be bought, but this takes money. Without money, you

can still make the required items, but this takes skill. As a result, most people cut corners and jerry rig a Rube Goldberg device that does nothing but

entertain the experimenter. This is worthwhile, but it is not science and will not be believed by the world of science no matter how well the arguments

are constructed or debated.

I) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

L.Kowalski wrote (but not posted):

Yes, in comparison with Ed Storms and Michael McKubre we are amateurs. By "we" I mean people involved in Colorado-2, Paris-2,

and Colorado-3 experimens. Scott Little, in my oinion, belongs to a much higher category of researchers. This jugemen is based on his exceptional

technical skills, and on experience he gained on working with calorimeters. He cooperated with Mizuno but was not able to replicate excess heat. I am

dissappointed that the Texas-2 experiment must be delayed because they are investigating something else. I would feel much more comforteble about the

Colorado-2 results if Scott also obesrved the COPs significantel larger that unity.

For the time being I rely on the data collected in Colorado-2, plus private confirmations from about ten more recent tests (preliminary data from Paris-2

and Colorado-3 experiments). I already responded to the hint Ed made about

our “complete wasting of time.” I am not going to repeat this again on the CMNS discussion list. Nothing could be gained from this. We were not

“cutting corners” in the Colorado-2 experiment. We did what science teachers and students could do in a school lab (after reading units #252

and #253) . Now we are discussing ways to determine how much liquid is lost in the form of tiny droplets. One of these methods, or more, will be used

in subsequent experiments. What is wrong with this? Why should we stop now? We found potential sources of errors and we want to be sure that excess heat

is not an illusion. We need help and encouragement. I think that our simple device did a little more than “nothing.” What I am affraid of is

that people planning for the Paris-2, Colorado-3, Texas-2 and Marseilles-1 experiment are going to give up because the most senior CMNS researchers

are not providing as much help and uncouragement that I expected. I hope this will not happen.

O) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Jed Rothwell wrote:

You do NOT -- repeat NOT -- want anyone to do this as a science fair project! This experiment should not be done by high school kids or by people who do

not have safety equipment at hand, including goggles, a shower and so on. Let me reiterate what I said earlier, with emphasis: This experiment is

DANGEROUS. The electrolyte is toxic and it is boiling. The light from the cathode is so intense it will damage your eyes if you look at it too closely

for too long. On at least one occasion, a glow discharge cell has exploded violently without warning, releasing over 400 times more energy than was

input into the cell. This is far beyond the limits of chemistry -- there is no doubt the energy release was anomalous. It drove a glass shard about

1 cm into Mizuno's neck, next to the carotid artery, and the noise deafened him and his colleague for several hours.

I spent several days watching both Ohmori and Mizuno performed their versions of this experiment. Both of them are careful, and both have decades of

experience doing electrochemistry, but Ohmori's technique was so frightening to Mizuno that Mizuno refused enter the lab. "I will watch from out here,

" he said, standing out in the hall. "The way Ohmori does this scares the hell out of me." This was five years before his own cell exploded. . . .

K) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Ludwik Kowalski wrote:

(1) An explosion due to accumulation of hydrogen is much less likely to occur in an open Mizuno-type cell. (2) Nearly all chemistry experiments performed

by students must be supervised by teachers. If I were to supervise an open-cell-Mizuno-type student project I would used the open cell. And I would

insist of using a standard laboratory hood, plus protection glasses, etc. . Yes, safety aspects are very important. (3) Do you remember a report from

two high school girls who confirmed the COPs >1 in Louisiana two years ago? I do not recall any safety concerns being raised (at our conferences)

about open cell experiments by high school students. Why now? I would like to see several student reports about over-unity COPs each year. The fact

that these reports do not prove anything new would not bother me. At this stage we need confirmations, the more the better. And think about educational

and motivational effects of such projects on students.

L) * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Jed Rothwell:

This explosion [in Mizuno cell] was anomalous. It could not possibly have been caused by hydrogen, or any chemical reaction. I presume it was a runaway

cold fusion reaction, like the one that melted or vaporized Fleischmann and Pons' cathode in Feb. 1985. We should not kid ourselves about this issue

anymore. I have now seen five credible reports of anomalous explosions, four them clearly beyond the limits of chemistry. I think it has been established

that cold fusion can produce runaway reactions and explosions. It is my gut feeling that the glow discharge version is particularly prone to this,

because it sometimes produces large energy spikes very rapidly. I only hope cold fusion cannot be used to make a large-scale nuclear bomb, but no one

can be sure of that at this stage.

Click to see the list of links