Post-1945 Theater

Influenced by the drastic

events of WWII: 61 million lives (civilian and military) lost

- 1945 Bombing of Hiroshima, Nagasaki; liberation of Jewish

concentration camps; Estab. of USSR; Estab. of

United Nations; US military occupies Japan; US, France, Britain, and

USSR occupy Germany; France leaves Syria and Lebanon

- 1947 Indian

independence: Pakistan, India divided; Britain leaves Palestine

- 1949 Estab. of GDR,

People’s Republic of China; Beginning of Cold

War: NATO vs. Warsaw Pact

Post-modern theater vs.

Classical theater

1. Aristotle’s theater = Neoclassical

- Structure: 5 Act play

(Horace)

- Time: Action of play

occurs in one day

2. Postmodern theater: Fractured structure, time, and action; ‘lowly’

characters

The “Theater of the Absurd”

(term coinced by theater critic Martin Eisel in 1961)

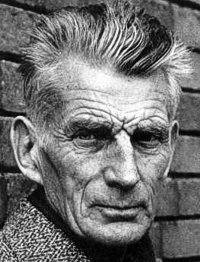

Samuel Becket Biography

(Brief Highlights)

- 1906: Born to Anglo-Irish middle class family

- 1923-27: B.A. in French and Italian from Trinity College in Dublin

(favorite author: Proust)

- 1928: Teaches at École Normale Supérieure in Paris;

meets Joyce and helps him with Finnegan’s

Wake

- 1930: Whoroscope (poetry)

- 1933: Psychotherapy in London after father’s death

- 1938: Novel, Murphy; living

in Paris permanently

- 1941: Joins French Resistance

- 1948-49: En attendant Godot

(Waiting for Godot)

- 1951: Molloy

- 1953: Waiting for Godot

produced at Théâtre de Babylone

- 1957: Fin de partie (End Game); prisoners in San

Quentin, CA watch a performance of Godot

- 1961: Marries

- 1964: Film

- 1969: Nobel Prize in Literature

- 1989: Dies same year as his wife

Existentialism FAQ

- “Nothing to be done” (Beckett

2).

-

WWII ended the international exchange of artistic, scientific ideas.

In fascist countries, the intelligentsia were brutally persecuted.

- In the postwar world, existentialism symbolized the isolated

individual and his abandonment.

- Existentialism served to brace the individual for survival in a

failed, fallen, and no longer trustworthy world.

-

"Existentialism is the set of philosophical ideals that

emphasizes the existence of the human being, the lack of meaning and

purpose in life, and the solitude of human existence . . .

Existentialism

implies

that the human being has no essence, no essential self, and is no more

than what he is . . .

In their treatment of ‘freedom,’ Existentialists imply that humans

are free to do as they please; after all, there good and evil do not

exist, only existence. But they also show that humans are a product of

situations of their own making" (Akram 1986).

- Cross reference Kierkegaard (1813-1855), Nietzsche (1844-1900 [“God

is dead”]), Camus (The Stranger), and Sartre (1905-80 [“Hell is

other people”])

- See this good site on Existentialism: http://www.bradcolbourne.com/existentialism.html

Works

Cited

Akram, Tanweer. "The Philosophy of Existentialism." New Nation

1986. Essays on Existentialism. Ed. Brad Colbourne.

<http://www.bradcolbourne.com/exist.html> Accessed Apr. 2007.

Interpretive

Questions

ACT I

1. What does Waiting for Godot seem to say about

language? Consider

Vladimir's carrot (16); Pozzo's commands (20) and need

for

permission (37); difficulties speaking (30); and/or

Lucky's speech (44-47).

2. What basic questions does Beckett’s play seem to raise about human

nature?

3.

Beckett subtitles

the play a “tragicomedy.” How does the tragic combine with the comic,

and the comic inform the tragic?

ACT II

1. What do the leaves

on the tree represent?

2. What lines,

gestures, and/or actions are repeated and by whom (from the first and

in the second act, for ex.)? What is the significance of these

repetitions?

3. Is the play set in

the past, the present, or the future? Is time (both the passing of time

and the setting) important here?

4. How does Beckett make an effective drama out of a play in

which nothing (apparently) happens? (Estragon: “Nothing happens, nobody

comes, nobody goes, it’s awful!” [43].)

Wendy C. Nielsen, "Waiting for Godot," Modern European Drama

(Spring 2007), Last updated Apr. 2007